Left Coast at the California Festival: CALIFORNIA VOICES

This Is What It Means

LEFT COAST CHAMBER ENSEMBLE AND THE SAN FRANCISCO GIRLS CHORUS

Left Coast and the San Francisco Girls Chorus team up to present a program which centers the voices of Californian women composers at the California Festival.

We interweave instrumental and vocal works by Pauline Oliveros, Gabriela Lena Frank, Reena Esmail, Gabriella Smith, Lisa Bielawa, and Ursula Kwong-Brown with the music of Nicolás Lell Benavides, Caroline Shaw, and Hildegard von Bingen. The two ensembles join forces to premiere a new work written for the occasion by Sarah Gibson.

Program includes:

Ursula Kwong-Brown - I see you, I hear you, I believe you

Gabriela Lena Frank - Picaflor from Two Mountain Songs

Gabriela Lena Frank - Canto para California

Lisa Bielawa - Forest from Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser

Nicolás Lell Benavides - A bird came down the walk (Pathways mentor)

Gabriella Smith - Carrot Revolution

Pauline Oliveros - Tree/Peace

Caroline Shaw - Dolce cantavi

Hildegard of Bingen - O Virtus Sapientiae

Sarah Gibson - This Is What It Means

Gabriela Lena Frank - Zapatos de chincha

Reena Esmail - The love of thousands

Artists

Anna Presler, violin

Phyllis Kamrin, violin

Matilda Hofman, viola

Leighton Fong, cello

And featuring the San Francisco Girls Chorus

This concert is generously sponsored by Susan Shalit and Mary Logger.

Left Coast presents two programs as part of the inaugural California Festival: A Celebration of New Music, which is happening throughout the state from November 3-19th: “This Is What It Means” and “Art Song and Keyboard Music of California”. We present more than twelve different Californian composers and span more than a century of music. How we listen to nature in a changing world is a current which runs through these concerts.

Meet the composers

-

Ursula Kwong Brown • I see you, I hear you, I believe you

This work was written in the wake of the ongoing #MeToo revelations, during which countless brave women and girls have come forward to tell their stories of sexual harassment and assault. It’s important to remember that for every person who tells their story, there are many, many others who feel they cannot, for all the reasons one can imagine. Never mind putting career at risk, all too often, victims are branded hysterics or liars – and this can feel as damaging as the original trauma. Research tells us that validation is essential to the healing process. There is nothing more powerful than knowing one’s story has been heard. This is why the lyrics of the piece repeat, over and over: I see you, I hear you, I believe you.

— Ursula Kwong-Brown

Gabriela Lena Frank • “Canto para California” from Contested Eden

I am a believer of human-driven climate change, reluctantly so. That is what four straight years of apocalyptic fires in your beloved home state will do. My husband and I diligently thin the forests on our property, installing water tanks and ponds, and covering edifices in fire-resistant stucco. We are regulars at classes at the fire station, and during fire season, have solar power at the ready for electrical outages, and emergency bags in the cars. And at the small music academy that I founded, my staff and I have begun leading classes for musicians about the climate crisis, and talk frankly about lifestyle changes needed in our field.

Contested Eden, in two movements, was a difficult project for me. A few months before the deadline, when asked if I could consider addressing the wildfires of California in my piece for the Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music, I was caught off guard. Then, I burst into tears and blurted out yes. What followed was a humbling period of apprehension against tackling the subject. When I did roll up my sleeves, I first wrote what could best be described as a melodramatic soundtrack for a theoretical film documentary on fire. Here’s the fire climbing up a Douglas fir: scurrying violins. There’s the ominous ascending column of smoke over hills before it sinks to the valley floor: horns in sixths to fifths to fourths to thirds to seconds, harmonized to descending bassoons. A solo flute could be the lonely bird hovering over a burned nest. Windchimes for…well, wind and maybe a charred kite. And riffing Ennio Morricone is always good for a firefighter’s vista shot surveying husks of homes against steam and ash.

This went on for a while, a couple of weeks. Ultimately, it was a useful, if mortifying, exorcism of tired cliches I’ll never show anyone, leaving behind just a couple of small usable germs: an original secular psalm, Canto para California, that forms an intimate lyrical first movement, followed by a second movement centered around the concept of in extremis, Latin for “in extreme circumstances.”

in extremis…What an apt description for life in California during the past four seasons, a Herculean effort of normalcy on the part of Californians while death is constantly imminent. Something inside, deep in one’s spirit, simply perseveres even while surrounded by unimaginable chaos and loss.

After an initial slow build-up, the heart of the second movement is a slowly moving violin line that elegiacally descends, over several minutes, moving from the stratospheres down to its lowest register before handing off to the violas, who eventually hand off to the cellos, who hand off to the basses. All the while, against this almost too-long falling arc, brief bits and pieces of earlier pieces I’ve authored come to life, albeit transformed, in the surrounding orchestral landscape before vanishing. Nothing coheres or makes sense, like memories that are of little help and comfort. That’s life in extremis.

Yet, the piece ends hopefully, a hint of the work’s opening and original secular psalm in tribute to the Eden that’s my beloved native state. So, while I honestly sometimes want to lie back in a comfortable bed of yesteryear, I recognize the past is going to stay there, and forward is what we’ve got. California’s never been a sleepy state, and an ultimately optimistic embrace of challenges to come is all I see for our future.

— Gabriela Lena Frank

Gabriela Lena Frank • Zapatos de chincha

This light-footed movement is inspired by Chincha, a southern coastal town known for its afro-peruano music and dance (including a unique brand of tap). The cello part is especially reminiscent of the cajon, a wooden box that percussionists sit on and strike with hands and feet, extracting a remarkable array of sounds and rhythms.

— Gabriela Lena Frank

Gabriela Lena Frank • “Picaflor” from Two Mountain Songs

Two Mountain Songs, premiered in a joint performance by the San Francisco Girls Chorus and the Young People’s Chorus, is inspired by Peruvian folk song from the northern Andes. It freely adapts poetry as collected by the folklorist José María Arguedas who was an advocate for the Quechua Indian people, the descendants of the once-powerful Incas. The lyricism, repetitive melodic forms, and rhythms are wholly original while inspired by the music of this small yet beautiful Andean nation.

— Gabriela Lena Frank

Lisa Bielawa • “Forest” from Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser

Vireo: The Spiritual Biography of a Witch’s Accuser is a made-for-TV-and-online opera, composed by Lisa Bielawa on a libretto by Erik Ehn and directed by Charles Otte.

All 12 episodes were broadcast on KCETLink’s Emmy® award-winning arts and culture series Artbound, as well as online for free, on-demand streaming, which was a first for the network. The Los Angeles Times called Vireo an opera, “unlike any you have seen before, in content and in form,” and San Francisco Classical Voice described it as, “poetic and fantastical, visually stunning and relentlessly abstract.”

Vireo is an Artist Residency Project of Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana, a unit of Cal State Fullerton's College of the Arts shepherded by Director and Chief Curator John Spiak. The unique multimedia initiative includes online articles and videos showcasing various facets of the production. Vireo is the winner of the 2015 ASCAP Foundation Deems Taylor/Virgil Thomson Multimedia Award and was awarded a prestigious MAP Fund Grant for 2016 through Grand Central Art Center. Bielawa and Otte recently received nominations for the 2018 Los Angeles Area Emmy Awards for their work on the project.

The eponymous heroine Vireo, played by soprano Rowen Sabala, is a fourteen-year-old girl genius entangled in the historic obsession with female visionaries, as witch-hunters, early psychiatrists, and modern artists have defined them. Based on Bielawa’s own research at Yale, then freely adapted and re-imagined by librettist Ehn, Vireo is a composite history of the way in which teenage-girl visionaries’ writings and rantings have been manipulated, incorporated and interpreted by the communities of men surrounding them throughout history. From the European Dark Ages, to Salem, Massachusetts, all the way to 19th century France and contemporary performance art, Vireo provides a thoughtful, sometimes-humorous look at the universal issues of gender identity, perception, and reality.

Vireo features the work of over 350 musicians including opera star Deborah Voigt, violinist Jennifer Koh, cellist Joshua Roman, mezzo-sopranos Laurie Rubin, Maria Lazarova and Kirsten Sollek, baritone Gregory Purnhagen, tenor Ryan Glover, drummer Matthias Bossi, soprano Emma MacKenzie and in the title role of Vireo, teenage soprano Rowen Sabala.

Additionally, the opera features the talents of notable groups and organizations from around the country including Kronos Quartet, the San Francisco Girls Chorus, Magik*Magik Orchestra, American Contemporary Music Ensemble, Alarm Will Sound, PARTCH, the Orange County School of the Arts Middle School Choir, and many, many more.

Gabriella Smith • Carrot Revolution

I wrote Carrot Revolution in 2015 for my friends the Aizuri Quartet. It was commissioned by the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia for their exhibition The Order of Things, in which they commissioned 3 visual artists and myself to respond to Dr. Barnes’ distinctive “ensembles,” the unique ways in which he arranged his acquired paintings along with metal objects, furniture, and pottery, juxtaposing them in ways that bring out their similarities and differences in shape, color, and texture. While walking around the Barnes looking for inspiration for this string quartet, I suddenly remembered a Cezanne quote I’d heard years ago (though which I later learned was misattributed to him): “The day will come when a single, freshly observed carrot will start a revolution.” And I knew immediately that my piece would be called Carrot Revolution. I envisioned the piece as a celebration of that spirit of fresh observation and of new ways of looking at old things, such as the string quatet—a 250-year old genre—as well as some of my even older musical influences. The piece is a patchwork of my wildly contrasting influences and full of weird, unexpected juxtapositions and intersecting planes of sound, inspired by the way Barnes’ ensembles show old works in new contexts and draw connections between things we don’t think of as being related.

– Gabriella Smith

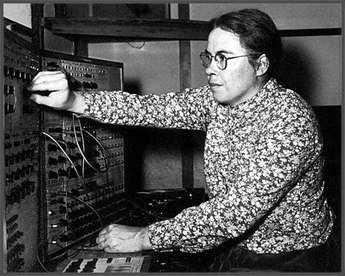

Pauline Oliveros • Tree/Peace

In one way or another, most of Pauline Oliveros’s music reflects on the processes of listening and attention–from her electronic compositions at San Francisco’s Tape Music Center in the 1960s (which became the Center for Contemporary Music under her direction at Mills College) to a TEDx talk she gave not long before her death titled “The Difference between Hearing and Listening.” In fact, Oliveros’s preoccupation with the practice of what has come to be called “deep listening,” began much earlier than her career as a composer; as a girl she attuned herself to the natural noises of insects, birds, and weather, and (in the manner of composer John Cage) to the quiet vibrations of everyday life. As writer Claire-Louise Bennett observes, “it was this erratic panoply of incidental and liminal sounds that captured her imagination, yet they couldn’t be expressed by conventional music notation.”

Some of Oliveros’s most famous compositions are in fact practices–actions that can be performed by anyone, regardless of musical training. Her famous series of “Sonic Meditations” contains scores that consist entirely of verbal instructions. “Take a walk at night,” one reads:

“Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears.” The Deep Listening workshops that have sprung up all over the world take their guiding principles from Oliveros’s profound experience of resonance, initially explored by her improvisation of sustained accordion tones in an underground cistern. The democratic aspect of Oliveros’s work is a crucial part of her legacy.

In Tree/Peace, however, it is a trio of professional musicians who are required to listen and act with fresh ears and minds.

Tree/Peace takes shape by means of a all-embracing core metaphor drawn from the natural world and a series of extremely (perhaps impossibly) precise instructions to the performers.

There are seven movements or sections, which together invite the performers to meditate on the life cycle of a tree.

1 – The Mystery of Propagation

2 – The Growth of the Seedling

3 – The Full Formation and Maturity of the Tree

4 – The Action of the Seasons

5 – The Magical Nature of the Tree

6 – The Death of the Tree

7 – Contemplation

Each of the seven movements consists of fourteen “events,” which alternate between “simple”

(devoted to a single tone, chord or sound) and “complex” (featuring improvised melodies, rhythms or harmonic progressions) based on the pitches printed in the score. The result is an irregular waxing and waning of musical activity–almost like the fluttering of leaves on a tree.

In an interview after one of the few recorded performances of Tree/Peace, cellist Anton Lukoszevieze remarked: “what struck me was the highly constructed pitch structure of the piece” which is magically dissolved into a constant “state of flux” where individual pitches “merge/emerge out of instrumental sounds (improvised) and timbral fluctuations.”

It would be an understatement to say that no two performances of Tree/Peace are alike. While the transitions between seven movements are marked by fleeting moments of instrumental unison, the constitutive events themselves may be short or long, with durations depending entirely on the players’ real-time reactions to the tiniest of nuances and shared gestures. Each rendering of the work thus depends on the mood and rapport between the members of the trio. In theory, the branching out of sounds in Tree/Peace will also depend on the tree metaphor at its root and thus, in a way, on the region, the season, the ecosystem of the performance. Is it a

redwood or a palm tree, an individual specimen or an abstract model of growth? The audience, too has a role to play in directing attentional energy toward the shifting web of sounds. As always with Pauline Oliveros, there is no such thing as passive listening–it is all about sound coming to life.

Hildegard • O Virtus Sapientiae

What a delicious irony that the earliest western music we can attribute to an individual composer bears the name of a woman: Hildegard von Bingen. She was a formidable figure–the founder of several religious houses, a central personage in the religious life of the German lands, and a respected authority in the fields of botany, medicine, theology, and of course music. Having entered a convent at an early age, she rose quickly to leadership in part because of her theo-political savvy but even more because of her extraordinary and ecstatic visions, for which she invented her own secret alphabet known as Lingua ignota, or “unknown tongue.” From these intensely personal vision experiences sprang a profound body of musical and poetic work, including the first known music drama, as well as influential writings in natural history. As Hildegard recalled near the end of her life, her visions centered on a “living Light... far, far brighter than a cloud which carries the sun.... And as the sun, the moon, and the stars appear in water, so writings, sermons, virtues, and certain human actions take form for me and gleam.”

Of Hildegard’s astonishing creative efflorescence, her music remains the most luminous and illuminating. Like most sacred music of her time and place, “O Virtus Sapientiae” is text centered, with a melody whose flexible, speech-like rhythms sanctify the act of recitation and infuse the all-powerful words with spiritual depth and delight. A sustained drone functions as Biblical bedrock and as foil for fanciful and provocative imagery. Here, Hildegard personifies Divine Wisdom as a mystic companion with a three-winged, trinitarian form. One wing springs from the earth, and a second soars above into the heights, inspiring a leap into the highest-vocal register in Hildegard’s musical output at the phrase “quarum una in altum volat.” The third wing–flying, whirling, and encircling–helps us make sense of her elastic musical phrases, evocative of the somewhat later Gothic style of architecture, in which arch upon arch vaults into the sky. There are as many ways to re-incarnate Hildegard’s music as there are forms of spirituality. Tonight’s performance by the San Francisco Girls Choir invites us to think about the young nuns at the abbey in Bingen, for whom Hildegard was the mother and model of both virtus (strength, energy or force) and sapientia (wisdom).

Nick Benavides • "A bird came down the walk"

A bird came down the walk holds a special place in my heart. Featuring the poetry of Emily Dickinson, it emulates some of the choral music I was singing in undergrad at Santa Clara University with dramatic shifts of mood, fractured text setting, and ornaments that land on glittering pandiatonic clusters. Originally premiered by San Francisco’s Musae, at the time led by Ryan Brandau, it is the first professional commission I ever received as a budding composer.

Like most American children, I was introduced to Emily Dickinson’s poetry through an English class in high school. When it was time to memorize poetry, I chose Emily Dickinson because her mysterious life intrigued me almost as much as her beautiful prose. Being from New Mexico, few things felt more foreign to me than 19th century New England, but her quietly rebellious nature stood out to me. Before I ever started working with living poets and librettists, I would draw on poems that I had memorized years before. It’s simple in premise: the speaker is watching a bird, which eats a worm, drinks dew, and hops out of the way of a beetle. She offers a crumb, but it takes to the skies and disappears, rowing himself softer home, as though he were a boat in the ocean. Hearing this piece reminds me of being in undergrad, with all the time in the world to sit in a park, enjoy watching wildlife, and let my imagination run wild.

— Nicolás Lell Benavides

Reena Esmail • The love of thousands

This is one of those stories that has the aura of a myth, but sometimes these little miracles happen to each of us.

One afternoon in the summer of 2018, I was at the Corona Institute for Women, a women’s jail just outside of Los Angeles doing a concert of some of my choral work, when a Catholic nun who happened to be visiting from Minnesota introduced herself to me. We connected immediately and deeply. At the end of our conversation she said, “I heard this phrase somewhere, and I feel you must set it to music. I don’t know where it’s from, but I think it will speak to you.” And she made me write down these words into my phone: “You are the result of the love of thousands.”

That interaction, and that phrase, stayed with me. I later researched it and found its author, the incredible Native American poet Linda Hogan. I set it first for San Francisco Girls Chorus, and revised it substantially into this SATB version of the work. The message is so true, and so hopeful. Each one of us exists in this world because of generations of ancestors, and also because of countless people who have shaped the course of our lives in ways we cannot begin to enumerate. It is miraculous.

Addendum: The week of the premiere of this piece, after much searching, I finally found the Catholic nun who had first shared the text with me. It was Sister Joanne Dehmer, who lived in Minnesota. But by chance, she was visiting Los Angeles again, and we reunited. The miracles continue.

— Reena Esmail

Caroline Shaw • Dolce cantavi

"for 3 voices (SSA) | duration: 3 minutes

text by Francesca Turina Bufalini Contessa di Stupinigi (1544-1641)

commissioned and premiered by TENET (Jolle Greenleaf, Molly Quinn, and Virginia Warnken Kelsey performing) available on recording: TENET's The Secret Lover"

Sarah Gibson • This is what it means

From an excerpt of Madeline Miller’s novel, Circe:

This is what it means to swim in the tide, to walk the earth and feel it touch your feet. This is what it means to be alive.

I read Circe earlier this year and was immediately struck by the excerpt I use as text in this piece. It comes from a section at the end of the novel in which the heroine finally finds peace and I connected to its concise but vivid description – life, it seems to argue, is rooted in our tactile relationship to our natural environment.

– Sarah Gibson

PRESS RELEASE - coming soon

>> VACCINATION & MASK POLICY

Proof of COVID-19 vaccination and masking are no longer required at these venues.

Image credit: Copyright Henry White, used by permission of Artist. Henry White is a landscape painter working in oils. These are some of his paintings of the oaks, hills and skies of our beautiful Bay Area and beyond. The banner image is a detail of Southern Sierra from Mt. Lamarck.

Saturday, November 4, 2023, 7:30 PM

First Presbyterian Church of Berkeley

2407 Dana St

Berkeley, CA 94704

Sunday, November 5, 2023, 4:00 PM

San Francisco Conservatory of Music

50 Oak Street

San Francisco, CA 94102