Up Next!

Exuberance and brilliance from young composers

Sky Macklay - Canon Cadenza Cadence Cluster - World Premiere

This commission has been made possible by the Chamber Music America Classical Commissioning Program, with generous funding provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

Sarah Westwood - Things You Don't Yet Know You Feel

2020 Left Coast Chamber Ensemble Composition Contest Winner

Carlos Simon - Lickety Split

Johannes Brahms - Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25

Left Coast Chamber Ensemble (LCCE) kicks off its 30th anniversary concert series with Up Next!, a concert celebrating the exuberance and brilliance of young composers! This program runs the gamut of musical emotions. Sky Macklay’s new rhythmically driven and jazzy string quintet contrasts with Sarah Westwood’s reflective introspection and Carlos Simon’s quirky and humorous musing on his childhood memories. The concert finishes with Brahms’ stormy and passionate first piano quartet, which includes the brilliant Gypsy Rondo.

Sunday, September 18, 2022, 7:30PM

Hillside Club

2286 Cedar Street, Berkeley, CA 94709

Monday, September 19, 2022, 7:30PM

San Francisco Conservatory of Music

50 Oak Street, San Francisco, CA 94102

The Composers

PROGRAM NOTES

Sky Macklay, Canon Cadenza Cadence Cluster

Sky Macklay (b. 1988) is a composer, oboist, and installation artist based in Baltimore. Her music is conceptual yet expressive, exploring extreme contrasts, surreal tonality, audible processes, humor, and the physicality of sound. She has been commissioned by Chamber Music America (with Splinter Reeds), the Fromm Foundation at Harvard University (with Ensemble Dal Niente), the Barlow Endowment (with andPlay), and The Jerome Fund for New Music (with ICE saxophonist Ryan Muncy). Sky’s work has also been recognized with awards and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, The American Academy of Arts and Letters, ASCAP, and Civitella Ranieri. Recent projects include an opera set in a uterus and three interactive installations of harmonica-playing inflatable sculptures. Sky teaches composition at the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, and her music is published by C. F. Peters. She spent much of 2021 in Paris as a fellow at the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination.

Canon Cadenza Cadence Cluster is a Freewheeling Fantasia of Fundamental Figures a Clownish Contrabass Concerto of sorts.

“I wrote the bulk of this piece while I was at MacDowell, an artist residency in New Hampshire. I was toying with the idea that the bass's role in classical music, while important and foundational, is often predictable or formulaic. I wanted to use that stereotypical role as a starting place, but to let the bass rebel from there. The form uses a sort of "ritornello" made from a chain of applied dominants anchored around three canonic melodies. I enjoyed experimenting with these traditional musical materials in a way that blurs and stretches them into a more surreal soundscape.” - Sky Macklay

cARLOS sIMON, lICKETY sPLIT

Described by the Los Angeles Times as a composer who “refashions musical history as excitable new realms with an unmistakable musical purpose essential for our times,” Carlos Simon is a multi-faceted and highly sought-after composer. His music ranges from concert music for large and small ensembles to film scores with influences of jazz, gospel, and neo-romanticism.

Recent commissioning highlights include premiere works with New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Los Angeles Opera, Washington National Opera and the Kennedy Center, an organisation with whom he has the title of Composer-in-Residence. His work has also been performed at the 2021 Ojai Festival by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra and at the Hollywood Bowl by the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra.

“As young boy, I worked with my grandfather during the summers paving driveways in Rocky Mount, Virginia. He was a task master. Things had to be done the right way and with haste when he asked for it in his own playful way. He would say, “Pull those weeds up likety split!” or “Shovel that dirt lickety split!” It was tortuous work during the hot summer days but ultimately proved quite lucrative at the end of the day when my grandfather paid me for the days work.

“This piece, in its whimsical character, draws on inspiration from that colloquial phrase, Likety Split, coined in the 1860s. It meant to do something quickly or in a hurry. I used the rhythmic syllabic stresses of the phrase as a main motif for the piece. (li-ke-ty split) To create a playful mood, I used bouncing pizzicato lines in the cello part over wildly syncopated rhythms played by the piano. Harmonically, the central idea moves in parallel motion in thirds between the voices. As the piece develops to an agitated state, both instruments relentlessly rhythmically drive to a climatic ending - done so in a lickety split fashion…” - Carlos Simon (Source)

Sarah Westwood, Things You Don't Yet Know You Feel

Sarah Westwood (UK) writes acoustic and electronic music. She is event co-ordinator and guest artist for Estalagem da Ponta do Sol Residency for Contemporary Music and Electronics Madeira since 2017 and is a composer-in-residence for Illuminate Women's Music 2019.

Sarah is drawn toward memory and intuition as a source for her music, and collaborates in dance, video, theatre, installation, as well as composing concert works. Collaborators include Eleven Farrer House (dance), LA based Moses Hacmon (artist/architect) and Georgie Lorimer (poet).

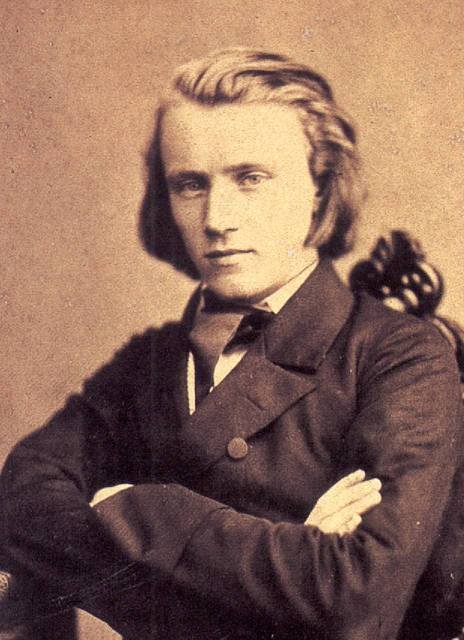

Johannes Brahms, Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25

I. Allegro

II. Intermezzo: Allegro ma non troppo – Trio: Animato

III. Andante con moto

IV. Rondo alla Zingarese: Presto

At age twenty-nine, the young composer Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) found himself at a turning point, perhaps even a moment of crisis: he was leaving the urban centers of northern Germany for Vienna–the city of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven. This was not a move to be taken lightly. When he was only ten, in his native Hamburg, his debut concert had featured chamber works by Mozart and Beethoven. When he was only twenty, Robert Schumann had hailed him as a genius, destined to inherit the symphonic mantle of Beethoven. Brahms, who had set up shop in Dusseldorf in order to be close to Robert Schumann and his wife Clara, protested against the “extraordinary expectations” that now lay heavy on his shoulders. Yet he set his sights on Vienna, and the work he chose to introduce himself to the Viennese public was his Piano Quartet No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 25.

When he offered up this Quartet to the audience at Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of the Friends of Music), Brahms was positioning himself as a pianist to be reckoned with–indeed it usually takes an alliance of all three of the string instruments to hold their own against his authoritative keyboard writing. He was also pledging his allegiance to the lineage of Mozart, Beethoven, and Robert Schumann himself, while also sidestepping the string quartet (the genre of chamber music most identified with Beethoven). This balancing act was successful. Joseph Hellmesberger, the violinist who participated in the Viennese premiere, proclaimed after reading through the score: “This is Beethoven’s heir!”

The composition had not come easily to Brahms, with drafts dating from a five-year period between 1856 and 1861, when the quartet finally received its premiere in Hamburg. The piano part was taken by Clara Schumann, and it was she who suggested the quintessentially Brahmsian title “Intermezzo” for the wistful second movement. It is an epic score, with a leisurely unfolding reminiscent of Franz Schubert, particularly in the opening Allegro. American critic and composer Daniel Gregory Mason linked this “prolixity” to Brahms’s “impetuous youth,” writing: “The melodies tumble over one another’s heels, spring out of each other as they run. Indefatigable renewal of energy, amplitude of development, luxuriance of thought.... This is still the music of youth, though the youth be that of a Titan.”

Uniting this melodic profusion are countless subtle connections. Perhaps most remarkable is a penchant for rising or falling half-step figures, present throughout the score and audible already in the second pair of notes in each of the opening bars. Fully on display are the two types of rhythmic subtlety Brahms liked best. One might be considered “horizontal,” consisting of fluid or ambiguous meters–what Mason called Brahms’s “taste for the phantasmagoria of shifting rhythms.” The other, the “vertical,” involves the superimposition of different divisions of the pulse (most typically two against three), heard to lovely effect in the sublimely lyrical passages of the inner two movements of the Quartet.

If the first three movements show Brahms coming of age and staking a claim on the classical tradition, the Quartet’s final movement, the “Rondo alla Zingarese” or “Gypsy Rondo” is a more straightforward souvenir of the composer’s youth. In the early 1850s, he befriended Hungarian violinist Ede Reményi. Their concert tour of 1853 introduced Brahms to Franz Liszt and to Joseph Joachim, violinist and composer, who became a lifelong friend and also introduced Brahms to the Schumann household. Audiences today delight in Brahms’s famous Hungarian Dances, with their rhythmic verve, asymmetrical phrases, and rhapsodic string figurations. But the “Rondo alla Zingarese” came first and it was largely responsible for the popularity of the Quartet as a whole. Couched in between statements of its vigorous and catchy refrain are evocations of folk fiddling and even the shimmering textures of the Hungarian cimbalom, a type of hammered dulcimer. Small wonder it has inspired numerous arrangements, including an orchestration by Viennese modernist Arnold Schoenberg–like the Quartet as a whole, this finale has a creative energy that chamber music can scarcely contain. (Program Notes by Beth Levy)