Please Elaborate

John Dowland - Come Heavy Sleep

Benjamin Britten - Nocturnal for Guitar

Eleanor Alberga - Oh Chaconne!

Johannes Brahms - Lullaby

Eleanor Alberga - No-Man's-Land Lullaby for Violin and Piano

John Dowland - If my complaints could passions move

Benjamin Britten - Lachrymae for Viola and Piano

VIRTUAL CONCERT:

Monday, November 9, 2020, 7:30 PM

This event is free to join. Please RSVP for event link! We ask you to consider making a donation of $25, or whatever you’re able.

In Please Elaborate, composers offer new ways of looking at music from other times. Benjamin Britten’s Nocturnal for guitar and Lachrymae for viola and piano are instrumental elaborations on songs by John Dowland. In Oh Chaconne and No-Man’s-Land Lullaby, Eleanor Alberga gives us her take on the monumental Bach Chaconne and Johannes Brahms’ tender Lullaby.

Please join the performers for a brief “after party” on Zoom immediately following the concert.

Artists

Nikki Einfeld, soprano

Michael Goldberg, guitar

Phyllis Kamrin, violin, viola

Eric Zivian, piano

Please RSVP for event link!

Event link will be in your confirmation email.

Program Notes

Oh Chaconne! (2015)

Eleanor Alberga

Notes by the composer

The original version of this piece was commissioned by the Yorke Dance Project for choreography by Robert Cohan in 2015. The dance piece was called ‘Lingua Franca’ and my composition was to precede the Bach-Busoni Chaconne, a piano transposition of Bach’s D minor Chaconne for solo violin. Both my work and the Bach-Busoni were performed by me at the dance premiere in London and in ongoing shows. I based my piece entirely on the Bach Chaconne and fitted it to the pre-choreographed movement with silences for Robert Cohan’s intermittent recorded speaking. I then decided to re-compose the work in early 2018 as a concert piece and ‘Oh Chaconne!’ is the result. Although the material is largely the same as ‘Lingua Franca’, I have cut and trimmed it to be more suitable for the concert hall.

In ‘Oh Chaconne’ there are 3 contrasting sections. Aspects of the Bach Chaconne are disassembled and worked in small detail at the start of the piece. Gradually, reassembled and more recognisable harmonies and passages from the Bach become apparent as the piece starts to build in momentum and driving energy. The third section enters as the music becomes tranquil in expectation of that pinnacle of musical composition to follow - the Bach Chaconne.

No-Man’s-Land Lullaby (1996)

Eleanor Alberga

Notes by the composer

Setting about writing a new work for violin and piano in the summer of 1996, I had planned a somewhat lightweight and predominately up-beat piece. However, I was to receive visitations which ensured that the piece which emerged as No-Man’s-Land Lullaby has neither of these qualities. Indeed, for me the work became a kind of acknowledgement of European-ness and a realisation that her two World Wars were part of my heritage also.

Visiting parts of Europe over that summer of ’96 I was struck by the almost unreal beauty of the landscapes, yet I received a heavy sadness in the atmosphere that took me back to the events of half a century ago, some of which had been played out against this very scenery. At the same time I was visited by a melody. It arrived unbidden and would not leave me alone. It seemed however, to offer comfort.

It was the imagery of the First World War that seemed finally to bring these things together, especially the image of men dying slowly and uncomforted in a place called No-Man’s-Land.

The piece is cast in three sections and is entirely based on the melody that emerges most identifiably towards the end.

John Dowland (1563–1626)

Come, Heavy Sleep and If my complaints could passions move

by Scott Foglesong

Drop the names of prominent Elizabethan composers in front of your average music lover and a blank stare is likely to result: Thomas Campion. John Bull. Giles Farnaby.

But say “John Dowland” and expressions are likely to change. Ah … Dowland … as memories arise of exquisitely mournful songs for voice and lute, of refined love poetry and sweet resignation. Ah … Dowland. He produced a smattering of choral works, but it’s those lute pieces that have earned him his well-deserved immortality.

In 1597 Shakespeare wrote The Merry Wives of Windsor and Dowland published his First Booke of Songes or Ayres. That he was a successful musician is beyond doubt, but not everything had gone according to plan. He been rejected for the post of lutenist in Elizabeth I’s court several years previously, and would soon head to Denmark for a lucrative gig at King Christian IV’s court. He eventually settled back in England as a court lutenist to King James I. He died in 1626.

The two lute songs “Come Heavy Sleep” and “If my complaints could passions move” are exquisite examples of the sweet melancholy that was so integral to Elizabethan and Jacobean court culture. “If music be the food of love, play on” says Duke Orsino in Twelfth Night. “That strain again, it had a dying fall.”

Benjamin Britten (1913–1976)

Nocturnal for Guitar and Lachrymae for Viola and Piano

by Scott Foglesong

John Dowland’s lute songs have provided fodder to generations of composers, none more so than Benjamin Britten, icon of 20th century British music and a writer of extraordinary skill and grace. Each of the two Dowland songs on this program have inspired works by Britten, the first being his 1963 Nocturnal for Guitar, written for Julian Bream, that takes “Come, Heavy Sleep” through what might be called reverse variations: Over eight separate movements, the variations come progressively closer to Dowland’s original, which is finally stated unvaried for the final movement.

Likewise, Dowland’s “If my complaints could passions move” underpins Britten’s Lachrymae for Viola and Piano, Op. 48, his only mature work for viola and piano. (There’s a later version for viola and string orchestra.) Like the Nocturnal, the Lachrymae is also a series of variations on the Dowland song, and like the Nocturnal, the Lachrymae eventually reveals the Dowland song in a relatively unadorned form.

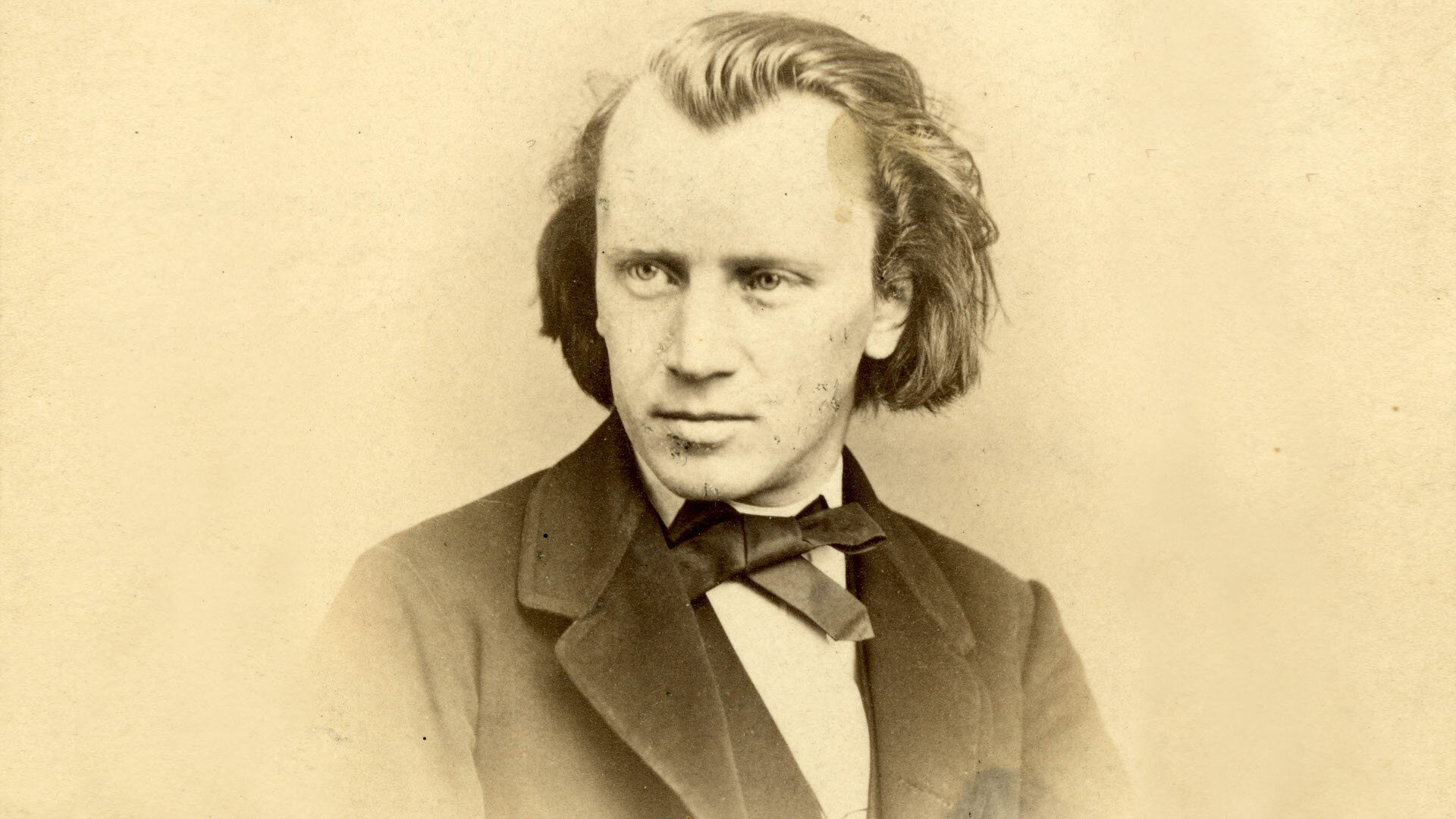

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Wegenlied, Op. 49, No. 4 (Lullaby)

by Scott Foglesong

Brahms’s Opus 49 consists of five lieder, i.e., art songs for voice and piano. No. 4 in the collection is one of Brahms’s most familiar works, the Wegenlied, or “Lullaby”, its text taken from the popular 19th-century collection of German folk poems, Des Knaben Wunderhorn—poems more associated with Gustav Mahler than Brahms.

The “Lullaby” is one of those pieces that seem to have always been here, much like Silent Night or Happy Birthday. But somebody wrote it, and not only was that somebody Brahms, he also recycled it (after a fashion) in the first movement of his Second Symphony. Everybody has sung it everywhere, and not just professional lieder singers either: Frank Sinatra gave us a wonderful rendition, as did Bing Crosby, Rosemary Clooney, and Kenny G.

Review

San Francisco Classical Voice: Left Coast Chamber Ensemble Pairs Modern Works With Their Early Antecedents (Nov 16, 2020)

Soprano Nikki Einfeld sang with exquisite sensitivity to Dowland’s musical setting and text.

Guitarist Michael Goldberg skillfully captured the mood of each variation

Violinist Phyllis Kamrin and pianist Eric Zivian brought both pathos and passion to the performance of both works.

Soprano Nikki Einfeld and guitarist Michael Goldberg performed Dowland’s exquisite song with emotional directness and grace. Violist Phyllis Kamrin and pianist Eric Zivian captured every nuance of Britten’s subtle and evocative score.

Banner image: Vivian Sachs